Columbia Sportswear North America, Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., Appeal Nos. 2021-2299, -2338 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 15, 2023)

In a decade-old case that has raised a number of issues relating to design patents over two separate appeals, the Federal Circuit addressed a matter of first impression concerning the scope of prior art relevant to an infringement analysis. The Court also clarified the law on other design-patent issues. Ultimately, the panel, in a 34-page opinion by Judge Prost, remanded the case for a second retrial on the issue of design patent infringement, finding that the district court, during the first retrial, had erred in formulating its jury instructions following the first appeal.*

Background

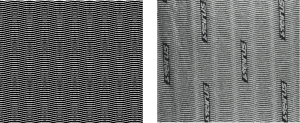

Columbia Sportswear’s D’093 design patent claims the ornamental design of a “heat reflective material.” The patent relates to Columbia’s use of materials with a metallic layer that reflects body heat in its Omni-Heat® line of outerwear products. The design at issue is a wavy-line pattern. In 2013, Seirus launched its HeatWave line of products in competition with Columbia’s Omni-Heat® products. HeatWave products had an internal lining that reflected body heat and used a wavy-line design broken up by Seirus’s logo. A comparison of the two designs is shown below:

In 2016, the district court granted summary judgment of infringement. Seirus had offered prior art to be considered as part of the infringement analysis, including fabrics with wavy lines. The district court found the majority of those fabrics—including fabrics for century-old radial tire technology—to be irrelevant as “far afield” from the heat-reflective material claimed in the patent. Even for one prior art reference that the district court did consider, the district court found it to be different enough to avoid raising a dispute of material fact concerning infringement. And, following the Federal Circuit’s opinion in L.A. Gear, Inc. v. Thom McAn Shoe Co., 988 F.2d 1117, 1124 (Fed. Cir. 1993), the district court disregarded the Seirus logo as part of his analysis. At a subsequent trial, a jury awarded Columbia approximately $3 million as disgorgement of Seirus’s profits, pursuant to Section 289.

Columbia I

Seirus appealed both the finding of infringement and the award of damages. In 2019, the Federal Circuit reversed in Columbia Sportswear North Am., Inc. v. Seirus Innovative Accessories, Inc., 942 F.3d 1119 (2019) (“Columbia I”), holding the district court erred in awarding summary judgment of infringement. The Court found that the district court usurped the jury’s fact-finding ability by finding that the prior art was not similar enough to the accused or patented designs. The Court also reversed the district court’s consideration of the Seirus logos, cabining its prior decision in L.A. Gear, and holding that L.A. Gear “does not prohibit the fact finder from considering an ornamental logo, its placement, and its appearance as one among other potential differences between a patented design and an accused one.” (Emphasis in original). Having reversed on infringement, the Court declined to reach Seirus’s damages issues, and remanded for a second trial on infringement. We wrote up the Federal Circuit’s opinion as our Case of the Week in November 2019, here.

The Remand Trial

In advance of the remand trial, Seirus sought to introduce all of its alleged prior art with wavy lines. Columbia objected, in part because the district court had already ruled that most of it was “far afield” of the heat-reflective materials at issue in the case. The district court ultimately allowed any prior art into the case provided it was “fabric.” The district court evaluated whether certain prior art—including plastic sheeting—constituted “fabric.” The district court also declined to give Columbia’s proposed jury instructions concerning the scope of relevant prior art in the infringement analysis, and prohibited Columbia from asking any questions or making any argument distinguishing the prior art on the basis that it was not a “heat reflective material.”

The district court also refused to give jury instructions informing the jury how to consider the Seirus logo in the analysis. This issue was critical because both the standard for design patent infringement and the standard for trade dress infringement are based on “confusion,” but trade dress considers confusion as to source, and a logo properly identifying the true source of the product can avoid trade dress infringement as a matter of law. But design patent infringement considers only a comparison of the two designs.

At trial, Seirus prominently introduced multiple prior art “fabrics” with wavy lines, including patents for plastic sheeting and radial tires. Seirus also argued to the jury that it should not find infringement because Seirus’s logo told consumers that Seirus was the source of the product, not Columbia, thus there could be no confusion. In other words, Seirus invoked trade dress principles to argue no confusion. The jury found no infringement, and Columbia appealed the district court’s jury instructions, as well as its order prohibiting Columbia from arguing whether any of the prior art was a heat reflective material. Seirus again cross-appealed the damages issues.

Columbia II

The case was argued in January 2023, and the design patent community has been eagerly awaiting the result. The case promised to answer at least one question that had never been answered in the century and a half that prior art had been used in a design patent infringement analysis: What is the proper scope of “prior art” that can considered in such an analysis? The appeal also raised concerns flowing from Columbia I concerning the impact and consideration of a defendant’s logos on a product accused of design patent infringement. To the extent damages issues would surface, Seirus’s cross-appeal also raised numerous issues of first impression for design patent cases following the Supreme Court’s decision in Samsung Elec. Co., Ltd. v. Apple Inc., 137 S. Ct. 429 (2016).

The Federal Circuit’s opinion began with a lengthy explication of the law-of-the-case and forfeiture doctrines, considering the legal effect of arguments not raised in the first appeal. Both parties raised these issues in different respects in advance of the remand trial. Ultimately, the district court held that the correct doctrine to apply was forfeiture, not law-of-the-case. The difference, the Court said, was that law-of-the-case applied to matters decided in a first appeal, whereas forfeiture concerned matters not raised, and thus not considered, during the first appeal. Proceeding to the analysis, the Court concluded that Seirus’s failure to raise the district court’s determination that prior art was “far afield” of the patent claims might constitute forfeiture. That said, the Court exercised its discretion not to enforce the doctrine, particularly because the scope of prior art question was being reviewed afresh by the Court as a matter of first impression.

Seirus also raised a forfeiture argument, but the Court rejected Seirus’s argument because Columbia was victorious after the first trial, and had no duty to appeal any issues. Thus, it did not forfeit any arguments by failing to raise them. In addition, the Court rejected a judicial estoppel argument that Seirus had also raised.

Scope of Comparison Prior Art

Moving on to the prior art question, the issue is one unique to design patent law. Specifically, the Court has held that, when comparing a patented design with an accused product, it is important to consider it in the context of the prior art. As the Court has recognized, in that context, “the attention of the hypothetical ordinary observer will be drawn to those aspects of the claimed design that differ from the prior art. And when the claimed design is close to the prior art designs, small differences between the accused design and the claimed design are likely to be important to the eye of the hypothetical ordinary observer.” But what is the scope of art that should be used in this comparison? Is it only art of the same article of manufacture? Is it all art that predates the patent? Or is it something in the middle—akin to “analogous art” in the utility patent context, for example.

The Court recognized that the issue was a matter of first impression. Tracing the history of design patent law back to the Supreme Court’s opinion in Smith v. Whitman Saddle Co., 148 U.S. 674 (1893), the Court concluded that the scope of prior art applicable to the infringement analysis is limited to the same article of manufacture claimed in the patent. The Court relied in part on its decision in In re Surgisil, L.L.P., 14 F.4th 1380, 1382 (Fed. Cir. 2021), which held that only the same article of manufacture can anticipate. The Court was moved by the legal truism that anticipation and infringement use the same test. The Court also looked to the purpose of prior art in the infringement analysis, practical considerations, and historical practice. It concluded, “to qualify as comparison prior art, the prior-art design must be applied to the article of manufacture identified in the claim.”

The Court further held “that the district court erred by failing to instruct the jury as to the scope of the D’093 patent claim (design for a heat reflective material) and, relatedly, the proper scope of comparison prior art.” The Court further found the error was prejudicial, warranting a new trial.

Seirus had argued that “heat reflective” was functional language that should be excluded from consideration. The Court disagreed, writing that it “may safely clear up Seirus’s general misconception about the role of function in design patents.” The Court then provided a lengthy discourse on the difference between designs that are dictated by function and claims, like that here, that are merely applied to a functional product. But the Court did not reach the issue of whether Seirus’s proposed prior art should be excluded from consideration, finding that specific question was not raised on appeal. Seirus argued that all material is heat-reflective, citing principles of physics that all matter reflects at least a nominal amount of heat. Columbia cited the prosecution history of the patent, which defined “heat reflective material” as a particular type of structure in the apparel space. The Court suggested the district court may want to construe the claim before a second retrial, to assess whether Seirus’s proposed prior art was “heat reflective material.” But the Court did “feel compelled to note that the accused design here is not applied to just any material. It is instead applied to material (called HeatWave, of all things) that Seirus touts for its heat reflective qualities. . . . This might suggest that, at least in the minds of some, heat reflective material connotes something genuinely distinct from just any material.”

Logos on Designs

The Court also considered Columbia’s appeal with respect to jury instructions where a defendant puts their logo on the product. Some context here helps. Prior to Columbia I, the law was generally understood that a defendant could not avoid infringement by labeling. See L.A. Gear, 988 F.2d at 1126. Columbia I held that a jury can consider a logo placed on a product as part of the design. It is helpful to remember the standard for design patent infringement elucidated by the Supreme Court in Gorham Co. v. White, 81 U.S. (14 Wall.) 511, 528 (1871), the so-called Gorham standard:

[I]f, in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other. (emphasis added)

There is an interplay between the consideration of logos and the notion that infringement is based on deceiving an observer to purchase one product supposing it to be the other. In theory, a logo denominating the source of the products would help to avoid consumer confusion. That is, after all, the test for trade dress infringement. But design patent infringement is supposed to be limited to whether the accused design bears the patented design, not whether consumers would be confused by the source of the product. Because of the possibility that a jury would understand the Gorham standard to allow a noninfringement verdict where a product was sufficiently labeled to avoid consumer confusion, Columbia asked for a special jury instruction to guide the jury on how to consider the product’s logo in the infringement analysis.

Ultimately, the Court did not find any error with the district court’s jury instructions, which supplied the Gorham standard and did not instruct the jury otherwise on how to consider the logo. But the Court did provide a lengthy discussion about the differences between how logos are to be considered in the trade dress context (a logo clearly identifying the product’s source can be enough to avoid consumer confusion) and the design patent context (a logo can only be considered as an aspect of design; consumer confusion as to source is irrelevant).

Although the Court did not find error in the district court’s jury instructions, the Court was “not insensitive to Columbia’s overarching concerns” about the phrasing of jury instructions. It acknowledged that “the ordinary-observer test could be read as evoking concepts of consumer confusion as to source, given that it asks whether the resemblance between two designs ‘is such as to deceive [an ordinary] observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other.’ ” But, the Court held, “district courts are in the best position to decide whether and when to provide clarification in the course of conducting a trial.” Here, the Court found no legal error or abuse of discretion in declining to offer Columbia’s proposed clarifying instructions.

The Court did not disturb its holding in Columbia I, that a jury may consider a logo as part of a design.

* In full disclosure, this week’s Case of the Week was tried at the district court and argued in part at the Federal Circuit by the co-editor of Fresh From the Bench, Nika Aldrich.

The opinion can be found here.

By Nika Aldrich

ALSO THIS WEEK

Netflix, Inc. v. DivX, LLC, Appeal No. 2022-1138 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 11, 2023)

In another opinion concerning the “scope of relevant prior art” analysis—this time in the context of utility patents—the Federal Circuit vacated an inter partes review decision of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board finding that petitioner Netflix had failed to show that claims of DivX’s U.S. Patent No. 8,472,792 were obvious over the prior art. The ’792 patent is directed to methods of facilitating certain playback functionality in streaming media, and at issue on appeal was whether a prior art patent (Kaku) directed to compression methods for digital cameras and other video devices was analogous art. The Court found that the Board abused its discretion by finding that Netflix had “failed to identify the field of endeavor of either the ’792 patent or Kaku,” such that it “cannot demonstrate that Kaku and the claimed invention are in the same field.” Netflix had argued throughout its briefing that both the ’792 patent and Kaku were generally directed to issues concerning “AVI files” and “encoding and decoding multimedia files.” The Federal Circuit held that contrary to the Board’s analysis, Netflix was not required to use the “magic words” “field of endeavor” to advance its analogous art arguments. Accordingly, the Court vacated the Board’s decision and remanded for consideration of the question “based on the arguments fairly presented by the parties.”

The opinion can be found here.

By Jason A. Wrubleski

Apple Inc. v. Corephotonics, Ltd., Appeal Nos. 2022-1350, -1351 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 11, 2023)

In this case, the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded two inter partes review decisions which had found that petitioner Apple failed to show that claims of Corephotonics’ U.S. Patent No. 10,225,479 were unpatentable as obvious. The Court found that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s claim construction in one case was erroneous, and that its decision in the second case was based on a ground not raised by any party in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act.

The ’479 patent concerned a camera that creates portrait photographs. Among other things, the patent specified two cameras (one wide and one tele) that fuse images together to create a background that is very blurry behind the subject of the photograph. The patent claims a camera controller that outputs “the fused image with a point of view (POV) of the Wide camera by mapping Tele image pixels to matching pixels within the Wide image,” among other limitations relating to camera parameters, such as track length, focal length, and pixel size.

Apple’s first appeal concerned the claim term “fused image with a point of view (POV) of the Wide camera.” Apple contended that, given the specification’s disclosure, the fused image required that it retain a “Wide perspective” or a “Wide position,” which Apple argued was disclosed in the prior art. Corephotonics disagreed with Apple’s construction and argued that the fused image required both a Wide perspective and a Wide position, which was not disclosed in the prior art. The Board agreed with Corephotonics’ interpretation of the disputed claim term and found the prior art did not disclose the claim limitation as argued by Apple. The Federal Circuit reversed the Board’s construction, noting that the disputed claim term does not mention “position” or “perspective” and instead only states that “a” point of view of the Wide camera is required. The Court looked to the patent’s specification for assistance and found that a “Wide perspective” and “Wide position” were reasonably understood as two different types of a “Wide point of view.” The Court stated that the inventor “took pains in the specifications to describe different types of point of view” and decided that, with the fused image, only “a” point of view of the Wide camera was required. Given the lack of any indication that the claim should be construed more narrowly, the Court held that the disputed term required that the fused image contain either a Wide perspective or a Wide position point of view. The Court thus reversed the Board’s claim construction and remanded for further proceedings.

Apple’s second petition challenged the patent’s claims relating to the camera parameters, arguing that a combination of two prior patents made the claims obvious. The parties’ argument on this issue focused primarily on whether a skilled artisan would combine the prior patents and scale them down such that they would have the same characteristics required by Corephotonics’ patent. In passing, Corephotonics also took issue with Apple’s expert having made a typographical error in his declaration, because the error resulted in the expert’s camera parameters not accurately reflecting the performance of a scaled version of one of the prior patents. Apple did not respond to this alleged error in its reply brief, and Corephotonics did not mention the error again. The Board, however, focused on the typographical error and found that Apple had not met its burden that the claim was obvious. The Federal Circuit vacated this decision on the grounds that the Board based its decision on an argument to which Apple did not have fair notice. Specifically, the Court noted that the Board “focused almost entirely” on Apple’s expert’s typographical error, which Corephotonics referenced one time in its briefing, along with additional errors that neither Apple nor Corephotonics identified as material. The Court held this to be in violation of the APA’s requirement that parties be informed of the “matters of fact and law asserted” and that the Board base its decision “on arguments that were advanced by a party, and to which the opposing party was given a chance to respond.” The Court vacated and remanded the Board’s decision “for further proceedings that meet the APA’s requirements for notice and the opportunity to respond.”

The opinion can be found here.

By Alex Bish

This article summarizes aspects of the law and does not constitute legal advice. For legal advice for your situation, you should contact an attorney.

Sign up