Volvo Penta of the Americas, LLC v. Brunswick Corp., Appeal No. 2022-1765 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 24, 2023)

In its only precedential patent case of the week, the Federal Circuit held the Patent Trial and Appeal Board erred in finding a boat propeller system patent invalid as obvious. The Federal Circuit’s decision is an unusual opinion that found error in the PTAB’s consideration of objective indicia in the obviousness analysis. It is an example of the type of case where there may be a prima facie case of obviousness, with all factors satisfied, but with such strong real-world evidence of nonobviousness that those factors may inform the proper disposition of the case.

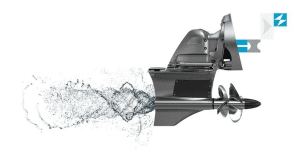

The patent concerns boat motors. Boat motors are characterized as outboard (i.e., an external engine on the stern of the boat), inboard (i.e., the engine and transmission are mounted in the hull, and a propeller shaft extends through the bottom of the hull), and “inboard/outboard,” wherein the engine is in the hull, but the drive unit is mounted outside the hull, typically on the stern. Such a configuration is also called a “stern drive” configuration.

In traditional designs, the propeller faces backwards, pushing the water backwards, propelling the boat forward. The patent at issue concerns a “tractor-type drive,” wherein the propeller faces forwards, thus pulling the boat forward. Specifically, the patent concerns a stern drive, tractor-type drive configuration. This configuration is beneficial in a number of environments, in part because the water in front of the propeller is unobstructed.

Volvo Penta, the owner of the patent, launched its product embodying its patent, which it calls Forward Drive. Volvo Penta’s Forward Drive systems have become very popular with the wake-boarding community, in part because of increased distance between the motor and the swimmer or wake-boarder at the back of the boat. Brunswick released a competing system and filed an IPR against Volvo Penta’s patent. As prior art, Brunswick asserted two patents. One of the patents was a Brunswick patent from 1952, which concerned an outboard motor that disclosed both rear-facing and forward-facing propellers. The other, a 1989 patent assigned to Volvo Penta, concerned a stern-drive with rear-facing propellers. Brunswick asserted that it would have been obvious to combine the forward-facing propeller from its 1952 patent with Volvo Penta’s 1989 patent directed to a stern-drive system.

The PTAB found it would have been obvious to combine the forward-facing propeller with the stern drive system, notwithstanding a variety of objective indicia submitted by Volvo Penta.

Volvo Penta appealed, challenging a number of the Board’s conclusions. The Court first affirmed there was sufficient evidence of a motivation to combine. For example, it was known that tractor-drive systems are more efficient and capable of higher speeds. This would have provided a motivation to combine. “Regardless whether” there are other ways to improve speed and efficiency, “that does not mean improved speed and efficiency cannot provide a motivation for the method of using a tractor-type drive. It is likewise not conclusive that speed may not be the primary or only metric by which recreational boats are measured. Substantial evidence supports a finding that speed is at least a consideration.” Moreover, the fact that both speed and efficiency would be impacted provided further motivation.

With respect to objective indicia of nonobviousness, one consideration was whether there was a nexus between the patented claims and the factors offered by Volvo Penta, such as commercial success. A nexus is presumed if the claim is coextensive with the commercial product embodying it. The Court affirmed the Board’s decision that there was insufficient evidence of coextensiveness to warrant a presumption of nexus. That said, the Court held that, even if the standards to warrant a presumption of nexus were not satisfied, there was still sufficient evidence of nexus. The Court found a lack of substantial evidence to support the Board’s contrary finding.

With respect to the objective indicia itself, the Court found error in the Board’s analysis. Specifically, the Board had considered multiple factors, including copying, commercial success, industry praise, skepticism, and long-felt but unsolved need. But the Board only gave “some weight” or “very little weight” to these factors. The Court held that the Board’s analysis, and its assignment of weight to different considerations, was overly vague and ambiguous.

For example, there was direct evidence of copying, which is normally considered strong evidence of non-obviousness. But the Board gave it only “some weight.” The Court walked through each of the categories of objective evidence and explained why the Board’s conclusion allocating, for example, only “some weight” was insufficient. The Court also criticized the Board’s balancing of the cumulative factors:

The Board fails to provide any explanation for that conclusion. Even if its assignment of weight to each individual factor was supported by substantial evidence (“some weight” for copying, industry praise, and commercial success; and “very little weight” for skepticism, failure of others, and long-felt but unsolved need), it stands to reason that these individual weights would sum to a greater weight. The Board does not discuss the summation of the factors at all other than to say, without explanation, that they collectively “weigh[] somewhat in favor of nonobviousness.

Ultimately, the Court vacated and remanded the Board’s decision, with direction to reassess the objective indicia of nonobviousness.

The opinion can be found here.

By Nika Aldrich

This article summarizes aspects of the law and does not constitute legal advice. For legal advice for your situation, you should contact an attorney.

Sign up