Ironburg Inventions Ltd. v. Valve Corp., Appeal Nos. 2021-2296, 2021-2297, 2022-1070 (Fed. Cir. April 3, 2023)

In this week’s Case of the Week, the Federal Circuit provided new guidance in applying the estoppel provisions of 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2), which provide that a petitioner in a completed inter partes review may not later assert in a civil action any invalidity grounds “that the petitioner raised or reasonably could have raised during that inter partes review.” The Court held for the first time that the burden of proof is on the patent owner to show that a challenger’s invalidity grounds are estopped, and that the standard to be applied is whether “a skilled searcher conducting a diligent search reasonably could have been expected to discover” the grounds. The opinion also provided a detailed discussion of indefiniteness that split the panel on the claims at issue, and further addressed issues pertaining to infringement, witness testimony exclusions, willfulness, and enhanced damages. The Court affirmed on all appealed grounds, except that it remanded the case to the district court to determine whether certain asserted invalidity grounds were estopped under its adopted standard.

The case involved Valve Corporation’s appeal from a more than $4 million jury verdict that Valve’s Steam Controller for PC gaming willfully infringed claims of Ironburg’s U.S. Patent No. 8,641,525, which is directed to a video game controller with “elongate member” controls on the back of the casing. Ironburg cross-appealed the district court’s denial of its motion for enhanced damages notwithstanding the jury’s finding of willfulness.

The jury verdict was reached following resolution of Valve’s partially instituted inter partes review* seeking to invalidate claims of the ’525 patent. Before the district court, Valve had asserted prior art invalidity both on grounds it had raised in its IPR petition but that had not been instituted (the non-instituted grounds) and on grounds Valve had not raised in its IPR petition (the non-petitioned grounds). The district court had determined in a pre-trial order that all of Valve’s asserted grounds were estopped under § 315(e)(2). The Federal Circuit agreed as to the non-instituted grounds because grounds “explicitly contained in the petition . . . were raised during the inter partes review” (cleaned up). The Court noted that following the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS (see footnote), Valve could have sought remand of the IPR decision for PTAB to consider the non-instituted grounds but declined to do so.

As to the non-petitioned grounds, however, the Federal Circuit found that the district court erred in implicitly placing the burden on Valve to show that it could not reasonably have raised the grounds in its IPR petition. First, the Court adopted a standard widely used among district courts that invalidity grounds “reasonably could have been raised” in an IPR petition if “a skilled searcher conducting a diligent search reasonably could have been expected to discover” them. Valve’s non-petitioned grounds had been raised in a later IPR filed against the ’525 patent by a third party, Collective Minds, but the record contained no evidence concerning whether Collective Mind’s search for prior art had been a “diligent search” or something more than diligent. (For example, the Court indicated that “a scorched-earth search around the world” for prior art was not required to avoid later estoppel.) The district court held this gap in the record against Valve, and concluded that Valve was estopped for failing to prove that its non-petitioned grounds could not reasonably have been raised in its own IPR petition. The Federal Circuit found this to be error, holding that the district court should have required Ironburg to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the non-petitioned grounds reasonably could have been raised. The Court reasoned that Ironburg was the party seeking to benefit from the estoppel provisions, and analogized statutory estoppel under § 315(e)(2) to an “affirmative defense” against invalidity on which the proponent should have the burden of proof. The Court remanded for further proceedings on this point, leaving it to the district court to determine whether the issue would require another trial or could be resolved through dispositive motion practice.

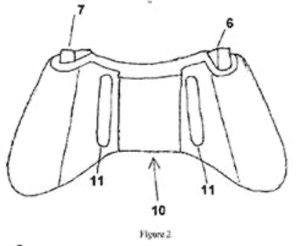

The Court also offered a detailed discussion of the alleged indefiniteness of limitations in the ’525 patent requiring infringing controllers to have controls on the back comprising “an elongate member that extends substantially the full distance between the top edge and the bottom edge.” As may be expected from the below images of the backside of the Steam Controller and Figure 2 of the ’525 patent, the parties hotly contested whether the patent adequately described such “elongate members,” what “substantially the full distance” was, or where along the “top edge” or “bottom edge” such distance was to be measured.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that none of the challenged limitations were indefinite. The Court reasoned that an “elongate member” was reasonably understood as referring to a member notably longer than it was wide, and that the scopes of both the terms “elongate member” and “substantially the full distance” were informed by the patent specification’s explanation that the purpose of these requirements was to ensure that users with varying hand sizes could comfortably operate the back controls with either their middle, ring, or little finger. The Court relied heavily on these statements of purpose and functionality, stating, “Those embodiments that allow the claim’s purpose to be effectuated are within the scope of the claims, while those that do not are not.” The Court further rejected Valve’s arguments that the patent provided no guidance regarding where along the top and bottom edges the “full distance” was to be measured, distinguishing its indefiniteness decisions in Dow Chemical Co. v. Nova Chemical Corp., 803 F.3d 620 (Fed. Cir. 2015), and Teva Pharms. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 789 F.3d 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2015), as turning on a lack of clarity as to how a measurement was to be made, explaining that in this case the parties agreed that the appropriate method of measurement “was simply to find the distance between two points.” The Court characterized the dispute over where the measurement was to be made as a dispute over infringement, not certainty as to claim scope, and said the jury was free to credit Ironburg’s expert testimony over Valve’s expert testimony as to whether Valve’s controls spanned “substantially the full distance” between the top and bottom edges.

Judge Clevenger dissented solely as to this latter point on indefiniteness, arguing that the majority made an arbitrary and unsupported distinction between “how to measure” and “where to measure”; that unreasonable uncertainty as to either should support a finding of indefiniteness; and that he would have found the claims of the ’525 patent to be indefinite. Responding to Judge Clevenger’s dissent, the majority caveated that “our decision today does not establish per se rules that teaching ‘how’ to measure necessarily renders a claim definite or that questions of ‘where’ are always issues of infringement.”

The Court also considered the parties’ challenges to the district court’s post-trial determinations concerning willfulness and enhanced damages. Valve had moved for judgment as a matter of law that its infringement was not willful or, in the alternative, for a new trial on willfulness. The district court had denied the willfulness point as “moot” because it had determined not to exercise its discretion to impose enhanced damages. The Federal Circuit found this determination to be error, since willfulness and enhanced damages are separate issues, but that the error was harmless because the jury’s determination of willfulness was supported by substantial evidence, specifically that Valve’s in-house counsel was reckless for failing to refer Ironburg’s pre-suit allegations to its designers or to attempt any design-around. The Federal Circuit also upheld the district court’s declination to award any enhanced damages, however, in view of a lack of evidence of any intentional copying or “pirating” of Ironburg’s invention.

The Federal Circuit also affirmed the district court’s determinations on the allowance and exclusion of certain proffered testimony, and found that the jury’s finding of infringement was supported by substantial evidence. The case was remanded for a determination of whether Valve’s non-petitioned invalidity grounds were estopped consistent with the Court’s opinion, and was otherwise affirmed.

The opinion can be found here.

*Valve’s IPR had been instituted prior to the Supreme Court’s decision in SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 1348 (2018), which held that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board must institute IPRs on all or none of the grounds asserted in a petition, and may not partially institute reviews.

ALSO THIS WEEK

SAS Institute, Inc. v. World Programming Ltd., Appeal No. 2021-1542 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 6, 2023)

In a high-profile appeal concerning computer software, the Federal Circuit waded into copyright territory. The case is the latest in a number of disputes across multiple continents between SAS and WPL concerning protections for SAS software. Of particular note here, a prior version of SAS software was in the public domain, so there was an issue concerning which elements of the software were subject to copyright protection. The district court ended up holding a “copyrightability hearing” to assess whether the software elements claimed by SAS were copyrightable. Judge Gilstrap from the Eastern District of Texas applied the abstraction-filtration-comparison test that had been adopted by the Fifth Circuit to evaluate the copyrightability of elements of SAS’s software. Ultimately, Judge Gilstrap found that SAS had failed to provide evidence concerning the filtration step, and held that the software elements at issue were not subject to copyrightability. SAS appealed and the Federal Circuit affirmed. A large number of amici filed briefs in the case, showing the level of interest in the case by the software industry. Judge Newman issued a 15-page dissent.

The opinion can be found here.

By Nika Aldrich

Joe A. Salazar v. AT&T Mobility LLC, Appeal Nos. 2021-2320, -2376 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 5, 2023)

In an appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, the Federal Circuit addressed whether the district court erred in construing “a microprocessor” and “said microprocessor” to mean one microprocessor that is capable of performing all the generating, creating, and retrieving functions recited in the patent claims describing technology for wireless and wired communications. After summarizing its previous holdings on the proper construction of the articles “a” and “said,” the Federal Court held that the district court properly interpreted “a microprocessor for generating,” “said microprocessor creating,” “a plurality of parameter sets retrieved by said microprocessor,” and “said microprocessor generating” to mean “one or more microprocessors, at least one of which is configured to perform the generating, creating, retrieving, and generating functions.” The court reasoned that, while the claim term “a microprocessor” does not require there be only one microprocessor, the subsequent limitations referring back to “said microprocessor” require that at least one microprocessor be capable of performing each of the claimed functions.

The opinion can be found here.

This article summarizes aspects of the law and does not constitute legal advice. For legal advice for your situation, you should contact an attorney.

Sign up