The U.S. Copyright Office has now released the second of four reports in its Copyright and Artificial Intelligence series, addressing the copyrightability of works created using generative artificial intelligence. The report can be found here.

The office had solicited public comment on five questions about this topic:

- Does the U.S. Constitution’s Copyright Clause permit copyright protection for AI-generated material?

- Are there circumstances under copyright law when a human should be considered the “author” of material produced by a generative AI system?

- Is it a desirable policy outcome to provide legal protection for AI-generated material?

- If that is a desirable policy outcome, should legal protection take the form of copyright, or should it be a separate, sui generis right?

- Does the Copyright Act require any revisions to clarify the human authorship requirement?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

- HUMAN AUTHORSHIP REQUIRED FOR COPYRIGHT PROTECTION

- NO COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR PURELY AI-GENERATED MATERIAL

- COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR WORKS OF HUMAN AUTHORSHIP PERCEPTIBLE IN AI-GENERATED OUTPUTS

-

- NO CHANGES TO COPYRIGHT ACT TO PROTECT AI-GENERATED OUTPUT

-

- NO ADDITIONAL OR SUI GENERIS LEGAL PROTECTION FOR AI-GENERATED OUTPUT

-

- Based on current technology, prompts by themselves do not support copyright protection for AI output.

-

- The fact that AI assists, rather than replaces, human creativity is not relevant to the copyrightability of AI-generated output.

- Analysis of human contributions to AI-generated outputs must be performed on a case-by-case basis.

EXISTING TECHNOLOGY

The report acknowledges that copyright law has dealt with previous technological advances by gradually but regularly expanding the types of creative output entitled to copyright protection. Photography, motion pictures, video games, and computers all presented challenges to the then-prevailing understanding of what constituted a copyrightable work. The development of generative AI systems continue the pattern of technological expansion, and raise challenging questions regarding the nature and scope of human authorship. This is particularly true because AI-generated outputs often resemble traditional copyright-protected works, such as written text and visual images. Nevertheless, the report states that resolution of these questions still requires a focus on human contribution, and whether it qualifies as authorship of expressive elements in the AI-generated output.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Proper analysis of the AI-copyright issue should begin with the U.S. Constitution, art. I, § 8, cl. 8: Congress can “secure . . . to authors . . . the exclusive right to their . . . writings.” An “author” is the person who translates an idea into a fixed, tangible expression. Originality (meaning both novelty and creativity), and not mere time and effort, is required for copyright protection.

To place the issue of AI-generated content in context, the report reviews prior case law applied to earlier technological advances. In the late 19th century case of Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, the Supreme Court determined that photographs could be protected by copyright because, for example, “posing the [subject] in front of the camera, selecting and arranging the costume, draperies, and other various accessories,” and “arranging the subject so as to present graceful outlines” constituted human-authored expressive elements of the product.

By contrast, content or material created by non-humans has consistently been denied copyright protection. In Urantia Found. v. Kristen Maaherra, alleged “divine messages” were not copyrightable, because “it is not creations of divine beings that the copyright laws were intended to protect.” Also, the ruling in Naruto v. Slater stated a monkey “is not an ‘author’ within the meaning of the Copyright Act.” In 2023, the DC federal district court in Thaler v. Perlmutter was the first to address copyright protection for AI-generated content directly. It held that an image autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine was not entitled to copyright protection: “copyright has never stretched so far [as] . . . to protect works generated by new forms of technology operating absent any guiding human hand.” That decision has been appealed.

Absent settled legal precedent regarding copyright protection for AI-generated output, the report found guidance from other types of copyright ownership. For content that results directly from a user prompt, the report settled on work for hire and joint authorship. In many cases when authorship is disputed among multiple parties, their relationship involves one party who provides suggestions and instructions, and another who physically creates the work. For example, the report looked at the CCNV v. Reid Supreme Court case, where the court held that merely commissioning a sculpture and providing detailed suggestions and directions to the sculptor did not make the commissioning party a coauthor.

With respect to copyright protection for human modifications, the report looked to derivative works. If the modifications show sufficient human creativity and can be identified apart from the AI-generated output, they could be entitled to copyright protection. In other words, where new technology merely assists humans in creating new expressive works, copyright protection is appropriate.

PROMPTS

Commenter Input. Commenters generally agreed that prompts themselves, if sufficiently creative, may be entitled to copyright protection, but AI images generated by simple prompts (e.g., “draw a picture of a mouse playing cards”) would not warrant protection. Comments varied with regard to protection for output based on more detailed prompts, however, including some that favored copyright coverage. Those commenters suggested a prompt could contain sufficiently specific details, and entail enough control over the expressive elements, that the output would reflect the prompter’s creative expression.

Many comments focused on the manner in which an AI system may execute a prompt. For example, the lack of predictability of AI output suggested a lack of control by the prompter over execution of the prompt. In such a “black box” system, not only users but also developers of AI systems are unable to predict outputs or the inclusion and exclusion of particular elements in those outputs. Similarly, where prompts and output reflect different media (for example, text to video), a number of commenters contended a prompter’s control over the execution of the prompt could only ever be indirect at best, and thus fail to qualify for copyright protection. Finally, the fact that an AI system may produce many different outputs in response to a single prompt was cited by several commenters as a potential argument against copyright protection.

Other commenters favored protection under certain conditions. For example, an iterative prompting process, in which the prompter makes successive revisions to the prompt so the output more closely aligns with the user’s creative vision, might support copyright protection. Others felt that “authorship by adoption,”—the act of selecting a particular output among many as the most accurate reflection of the creator’s vision—demonstrated judgment sufficient to warrant copyright protection.

Analysis. The report concludes that prompts do not constitute sufficient human control over the expressive elements of AI-generated output to warrant copyright protection. Instead, they function as instructions that convey unprotectible ideas. Even where detailed prompts might contain the user’s desired expressive elements, prompts currently do not control how an AI system processes those elements to generate output. This point is supported by the fact that identical prompts can result in multiple, differing AI-generated outputs.

The report cites joint authorship case law to support the conclusion that providing detailed directions or instructions, without control over how they are executed, is not sufficient for copyright protection. It cites the 1991 3rd Circuit case Andrien v. Southern Ocean County Chamber of Commerce for the proposition that joint authorship (including authorship for the party that provides instructions and guidance) is only warranted when the technological execution process is “rote or mechanical transcription that does not require intellectual modification or highly technical enhancement.”

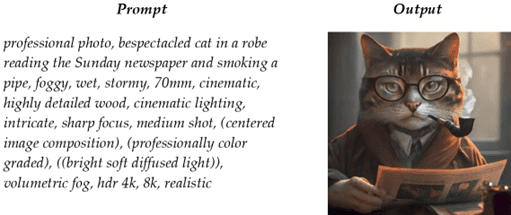

To illustrate the point, the report used a commercial AI system to create the following image with the prompt:

The report notes that the output image contains a number of elements not included in the prompt, such as the cat’s breed and coloring, size and pose, its type of clothing, and that it should have a human hand. In addition, certain elements from the prompt, such as a highly detailed wood environment, were not included in the output.

Further, in connection with the use of iterative, repeated prompts to revise AI-generated content, the report notes the selection of a single output among many is not itself a creative act. Thus, copyright protection is not warranted.

The report allows that AI systems could potentially be developed to the point where they empower users to exert sufficient control over the way the user’s expression is reflected in AI-generated output to qualify as “rote or mechanical.” However, evidence of current AI system operation does not exhibit that level of control.

EXPRESSIVE INPUTS

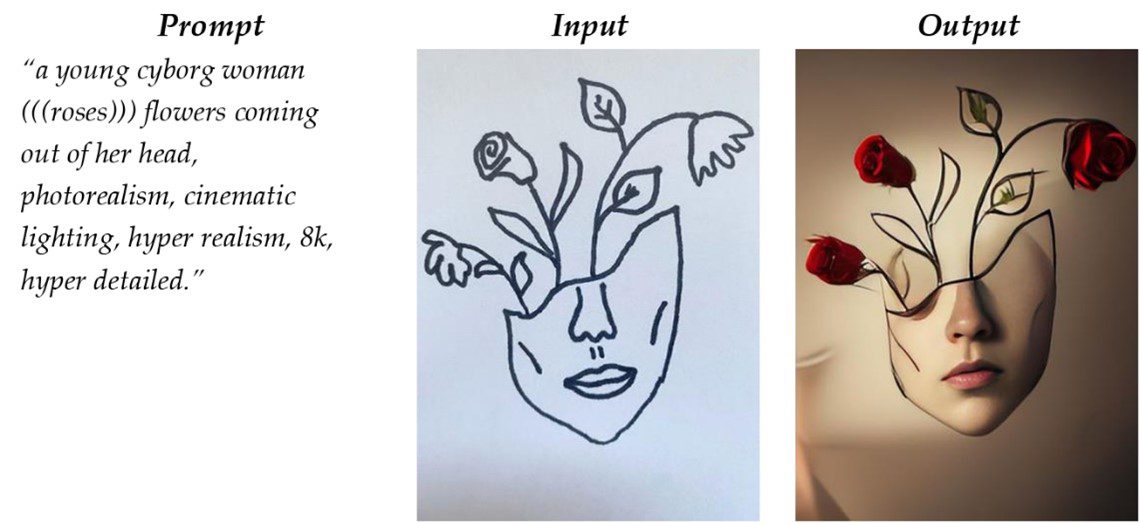

In some cases, AI prompts include actual copyrightable works. These constitute more than just complex instructions; an example would be a pictorial work provided to the AI system as specific guidance to create the desired output of the written prompt. The report notes an existing copyright registration for the following product, based on the following prompt and inputted drawing:

Because the input itself constitutes a copyrightable work, and is clearly reflected in the output, the Copyright Office registered the work, but only for the human authorship separable from the non-human expression.

MODIFYING/ARRANGING AI-GENERATED OUTPUT

The report looks to the law that pertains to derivative works to analyze opportunities for copyright protection with regard to modifications to or arrangements of AI-generated content. It notes that combining distinctly different components, such as human-created text and AI-generated images, into a book could result in copyright protection for the human-created facets of the work (in this example, the text and the selection and arrangement of the images).

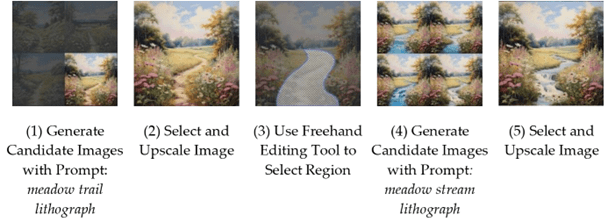

The report also finds that copyright would extend to the human-authored material even in instances where AI is used with a series of revised prompts to create a final image. An example from the report is shown here:

Further modifications through repetition of the editing process resulted in:

The report finds that such a process enables the user to exert sufficient control over the selection, arrangement, and content of the final output.

INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION OF AI-GENERATED OUTPUT

The report surveys the international landscape regarding copyright protection for AI-generated content, and concludes that all the countries that have addressed the issue require human authorship for copyright protection. However, various nations appear to hold constrasting conceptions of what qualifies as human authorship.

For example, the EU and Korea are unequivocal that purely AI-generated content is not entitled to copyright protection. Japan has announced a multifactor test that covers: (1) the amount and content of the instructions and input prompts by the AI user; (2) the number of generation attempts; (3) the AI user’s selection from multiple output materials; and (4) any subsequent human additions and corrections to the AI-generated work. In China, a 2023 case found that an AI-generated image was entitled to copyright protection, and the user who created it was the owner, given that the user applied more than 150 prompts that were tailored to produce a specific output. The court found these efforts demonstrated the image resulted from the author’s intellectual achievements and reflected his personal expression.

Other countries, including the UK, Canada, and Australia, are actively weighing the issue but have not yet issued official guidance.

POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

Providing Incentives. Commenters differed on which incentives ought to be created by protecting, or denying protection for, AI-generated content. Some suggested such protection would encourage the construction of more works, which in turn would further progress in culture and knowledge for the public good; others pointed to the current exponential growth of AI systems and technology as proof that no additional incentives are needed. Indeed, many commenters expressed concern that legal protection for AI-generated output would discourage “old-fashioned” creation of works by humans, given the relative speed and ease of generating the former.

The report concludes that no new protection, either under the Copyright Act or as a sui generis right, is required. It agrees with comments that noted the rapid development of AI systems and potential discouragement of human authorship. It also states that a proliferation of AI-generated content, spurred in part by protection, could make a search for inspiring or enlightening content more challenging.

Empowering Creators With Disabilities. Many comments noted that AI can support disabled persons who wish to create content, and that protecting AI-generated content would empower them. The Copyright Office expressed its support for all who create artistic works, including those with disabilities, but added that most of the comments which favored protection as a way to assist such creators focused on uses of AI systems as assistive tools. The report reiterates the position that assistive use of AI systems will not affect the copyrightability of completed works; as an example, it mentioned the use of an AI tool to create a vocal model for a musical artist affected by a stroke, and observed this had not prevented registration of a sound recording that features that AI-generated vocal model.

Combating International Competition. Several observers said that failure to protect AI-generated content would slow the development of AI technology and systems in this country, and cause the U.S. to fall behind other nations. Others warned the center of cultural intellectual property generation will shift to other countries who are more willing to protect AI-generated content. Without challenging those arguments, the report found the U.S. is bound by the Constitution and copyright principles, and therefore requiring human authorship is the preferred policy.

NEED FOR CLARITY

Several commenters suggested that greater clarity with regard to copyright protection for AI-generated content would benefit individuals and entities that create and claim to own such content. For example, commercial transactions would benefit from more certainty about the protected status of such works. Authors would benefit from knowing whatever they create using generative AI systems can be registered, licensed to other parties, and enforced. Legislation that articulates the scope of protection should be enacted, some commenters urged.

While acknowledging these points, the report concludes that legislation is not necessary, and suggests such action would likely not produce greater clarity. The courts will be the appropriate forum for clarity, given the highly specific nature of each claim for shielding of AI-generated content.

REMAINING REPORTS

The remaining two Copyright Office reports will cover training of AI models on copyrighted works, licensing considerations, and allocation of liability. They will be published in the coming months, and we will analyze and summarize them as they are released.

This article summarizes aspects of the law and does not constitute legal advice. For legal advice with regard to your situation, you should contact an attorney.

Sign up